As the New England Patriots and Seattle Seahawks prepare to face off at Levi’s Stadium on February 8, 2026, a parallel spectacle is in its final stages of preparation.

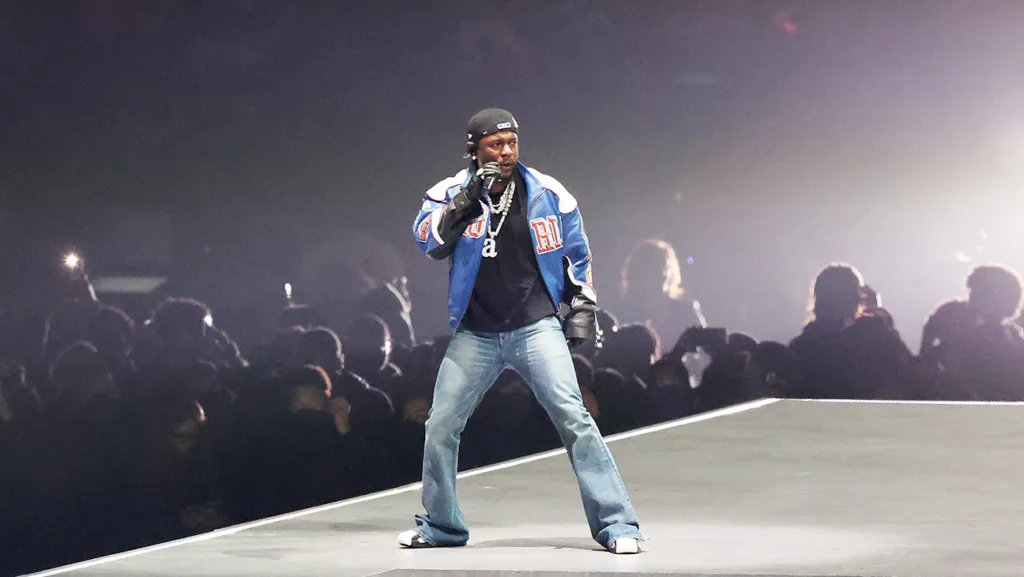

Bad Bunny, one of the world’s most-streamed artists, will headline the Super Bowl Halftime Show, performing for an audience exceeding 100 million viewers.

Behind the 13-minute concert lies a fascinating and complex economic reality: a multi-million dollar production funded entirely by the NFL and its partners, where the star performer receives essentially no direct fee.

The NFL’s no-pay policy: A tradition of exposure over fees

Contrary to popular belief, headlining the Super Bowl Halftime Show does not come with a superstar paycheck. The NFL maintains a long-standing policy of not paying performers for the pregame and halftime shows beyond what is required by union scale.

According to a 2025 Sports Illustrated report, 2024 performer Usher was paid a mere $671 for the actual performance day and about $1,800 for rehearsals. For an artist like Bad Bunny, whose tours and endorsements generate millions, this sum is symbolic at best.

The rationale, from the league’s perspective, is straightforward. An NFL spokesperson stated in 2016, “We do not pay the artists. We cover expenses and production costs”.

Entertainment attorney Lori Landew explained the artists’ viewpoint to Forbes, noting that “the halftime show at the Super Bowl remains a highly coveted spot for many artists… they… view their live performance as an opportunity to entertain an enthusiastic crowd and to share their music and their talent with millions of viewers”.

The league positions the unparalleled exposure as the primary compensation.

The real price tag: Multi-million dollar production budgets

While the artist may not receive a direct fee, the cost of mounting the halftime spectacle is staggering. The NFL shoulders the entire multi-million dollar production budget, covering everything from stage construction and audio engineering to pyrotechnics and personnel.

Recent shows have seen budgets range from $10 million to $20 million;

- The 2020 performance by Jennifer Lopez and Shakira reportedly cost approximately $13 million. This financed a collapsible 38-part stage, massive audio equipment on 18 carts, and paychecks for up to 3,000 staffers.

- Historical data shows Prince’s iconic 2007 performance had a $12 million budget, while Lady Gaga’s 2017 show cost $10 million.

- In some cases, artists have even contributed their own funds to realize their creative vision. For his 2021 performance, The Weeknd spent an additional $7 million of his own money to enhance the production.

These budgets finance a military-grade operation: a full concert is set up, performed, and disassembled in the span of about 30 minutes in the middle of the stadium field.

The technical marvel involves awe-inspiring elements, from Katy Perry’s mechanical golden lion to Lady Gaga’s descent from the stadium roof.

The calculated ROI: How artists profit from the platform

Artists accept the nominal fee because the halftime show functions as the single most powerful promotional engine in the music industry. The performance catalyzes an immediate and massive surge in audience engagement and revenue streams.

The most direct benefit is a dramatic spike in music consumption. Following her 2017 performance, Lady Gaga saw a 1,000% increase in her digital catalog sales. Justin Timberlake experienced a 534% rise in music sales the day of his 2018 show.

In the streaming era, this effect is even more pronounced. After Kendrick Lamar’s 2025 halftime show, his Spotify streams increased by 430%, while Usher saw a 550% surge following his 2024 performance.

Monica Herrera Damashek, head of label partnerships at Spotify, confirmed this pattern: “After a major live show, many fans head straight to Spotify. The same is true for the Super Bowl halftime show each year… This surge in streaming translates directly into increased revenue for artists and their teams”.

The show also serves as a launchpad for other lucrative ventures. Usher used his 2024 spotlight to promote his subsequent tour, which became one of the highest-grossing tours of the year, earning $88.5 million.

Furthermore, the visibility often leads to new endorsement deals, sponsorships, and commercial opportunities. For an artist like Bad Bunny, who is also a leading nominee at the upcoming Latin Grammys, the performance is a global platform to solidify his status and reach new audiences.

Labor and compensation: Ensuring fair pay behind the scenes

The conversation around compensation has not been limited to headliners. The NFL has faced criticism for its treatment of the hundreds of dancers and backup performers essential to the show.

An investigation by the Los Angeles Times revealed a two-tiered system where some dancers were paid while others were framed as “volunteers,” sitting unpaid in cold stadium bleachers during rehearsals.

Following backlash from the dance community, the union SAG-AFTRA intervened. The union stated, “SAG-AFTRA and the producers of the Super Bowl Halftime Show have met and had an open and frank discussion, and have agreed that no professional dancers will be asked to work for free as part of the halftime show”.

This agreement ensures that all background performers are compensated for their work, marking a significant step toward equitable labor practices for the massive production.

The enduring allure of the world’s biggest stage

From Michael Jackson’s 1993 performance that redefined the show’s potential to Prince’s legendary 2007 set in the rain, the halftime show has become a cultural landmark. For artists, it represents a rare opportunity to craft a legacy-defining moment seen by more people than any single concert in history.

The financial model of the Super Bowl Halftime Show is a unique exchange where traditional compensation is replaced by unmatched promotional capital.

The NFL invests millions to produce a spectacle that maintains viewer engagement during the game’s intermission, while the artist invests their time and talent for a platform that reliably turbocharges their career.

As Bad Bunny takes the stage at Super Bowl LX, he does so not for a paycheck, but for the chance to command the attention of the world, an opportunity that, in the modern music economy, is arguably worth more than any one-time fee.

In the high-stakes economy of attention, the halftime show remains the most valuable 13 minutes in entertainment.